In 1950 an offhand gift changed my life. Some fellow who worked in a Bay Ridge music store, a jazz fan, was getting rid of stuff; I can't remember why. Moving? Purging? He knew Dad, and he knew I had a budding interest in jazz. (At the time, I'd heard more Erskine Hawkins than Coleman Hawkins.) Dad and I went to his apartment and he gave me about twenty 78s from his collection. "Odds and ends," he called them. I remember them all, but these stand out:

- An album of "Unissued Duke Ellington" from the 1930s, my first taste of Ellington. My favorites were Blue Mood (Ellington later used the main strain for his celebrated Echoes of Harlem) and two small-group sides with Johnny Hodges, Rex Stewart, and Harry Carney: Tough Truckin' and Indigo Echoes. (Could such masterpieces really have been unissued?) I played these three sides obsessively for months, haunted by their beauty. They still get to me.

- An album of Bunny Berigan and Bud Freeman sides (some of which were cracked): Chicken and Waffles, You Took Advantage of Me, Blues, The Buzzard, Keep Smilin' at Trouble, and Tillie's Downtown Now. I liked all the soloists, but Bunny's drive, ideas, and tone on the trumpet knocked me out. So much so that I decided to make the trumpet my instrument.

It would be nice to report that this was the beginning of a rewarding career as a musician. I did take trumpet lessons, and kept it up through high school orchestra. (What the Fort Hamilton Philharmonic did to Wagner's Rienzi overture was cruel, even to a louse like Wagner.) I finally gave it up, flummoxed by triple-tonguing. But those "odds and ends," those 78s given to me in 1950 were enough to steer me into a lifetime's worth of musical joy.

When you give a gift, or give stuff away, you never know what's going to be a life-changer for someone. Brooklyn Girl and I were discussing this the other morning over coffee. She was talking about giving away old clothes. Think about it: some old suit or outfit might enable someone somewhere to dress properly for a job interview resulting in a job sufficient to send a son or daughter to college leading to a career in science or medicine resulting in...

"We're all connected," said Brooklyn Girl. We are, in ways we can't possibly imagine.

At this point the conversation was getting a little eerie, and then the Twilight Zone music kicked in, so we decided it was time for breakfast.

He left Brooklyn many years ago but Brooklyn never left him. His childhood was a rich gumbo of passions: the Dodgers, radio shows, comic books, 78 rpm records, stickball, punchball, movies, and of course the Dodgers. From these ingredients his life's main interests were formed: jazz, classical music, writing, and (still) baseball. Brooklyn also gave him Brooklyn Girl, who has been his best friend for more than half a century. One lucky kid.

Monday 28 February 2011

Duke Snider (1926-2011)

The Duke of Flatbush, Hall of Famer and last of the Boys of Summer, died yesterday. His obituaries have rightly focused on his 407 lifetime homeruns, his slugging exploits in the World Series, and his defensive skills. Were it it not for Ebbets Field's cramped dimensions, Snider would be remembered as much today for his DiMaggio-esque grace and range in center field as for his slugging.

But one Ducal feat has gone curiously unremembered. Until 1950, only two major leaguers in the twentieth century had hit four homeruns in one nine-inning game, Lou Gehrig and Chuck Klein. (Gil Hodges did it on August 31, 1950.) Snider came within a few feet of this amazing accomplishment. Not once. Twice. And both times he was thwarted by Ebbets Field's 38-foot-high right-field scoreboard and fence.

I was watching on TV the first time. It was Memorial Day, 1950, the first game of a morning-afternoon doubleheader against the Phillies. (That's right, a morning game.) After swatting three homers, in his last at-bat Snider sent a long, high drive to right field, seemingly Bedford Avenue-bound, but it caromed off the top of the scoreboard. It must have missed clearing it by five feet.

He came almost that close again, a few years later. This time I was there. In a high-scoring night game against the Braves, Duke had already hit three homers. With the crowd roaring for a fourth, he came to bat late in the game, and the Braves brought in a left-hander to face him. (I think it was Juan Pizarro.) Usually lefties gave Snider a terrible time, but on this occasion he connected and drove one toward the scoreboard. It was one of those line drives with lots of topspin, so it didn't have the necessary elevation. It caromed off the scoreboard at least half-way up. I think Duke got a long single out of it. In Yankee Stadium it would have been a homerun.

We remember you, Duke.

But one Ducal feat has gone curiously unremembered. Until 1950, only two major leaguers in the twentieth century had hit four homeruns in one nine-inning game, Lou Gehrig and Chuck Klein. (Gil Hodges did it on August 31, 1950.) Snider came within a few feet of this amazing accomplishment. Not once. Twice. And both times he was thwarted by Ebbets Field's 38-foot-high right-field scoreboard and fence.

I was watching on TV the first time. It was Memorial Day, 1950, the first game of a morning-afternoon doubleheader against the Phillies. (That's right, a morning game.) After swatting three homers, in his last at-bat Snider sent a long, high drive to right field, seemingly Bedford Avenue-bound, but it caromed off the top of the scoreboard. It must have missed clearing it by five feet.

He came almost that close again, a few years later. This time I was there. In a high-scoring night game against the Braves, Duke had already hit three homers. With the crowd roaring for a fourth, he came to bat late in the game, and the Braves brought in a left-hander to face him. (I think it was Juan Pizarro.) Usually lefties gave Snider a terrible time, but on this occasion he connected and drove one toward the scoreboard. It was one of those line drives with lots of topspin, so it didn't have the necessary elevation. It caromed off the scoreboard at least half-way up. I think Duke got a long single out of it. In Yankee Stadium it would have been a homerun.

We remember you, Duke.

Saturday 26 February 2011

Dixie and Kirby (Part 2)

1946, a few weeks later. I call this photo Me ‘n’ Kirby Higbe in Schul. Organized religion and I never really took to each other. My appearances at services were few, and even they required strenuous parental cajolery. But tell me Kirby Higbe will be signing autographs at the local synagogue and I’m there in a flash! I’ve even got an extra pen in my breast pocket, just in case Kirby’s runs dry in mid-autograph. Better safe than sorry. Meanwhile the other kids seem fascinated and delighted by Higbe’s uncanny ability to write his own name.

The more you know about Higbe the funnier the photo gets. He was what sportswriters called a “colorful” character. In 1946 we fans knew nothing about ballplayers’ private peccadillos. It seems Ol’ Hig had peccadillos aplenty, freely described in his autobiography The High Hard One. One story I’ve heard has him defending himself against some allegation with: “It must have been another Kirby Higbe.”

I often wonder what this picaresque character from Columbia, South Carolina is thinking as he performs his community-relations duties for the ballclub, signing and schmoozing in a little Brooklyn synagogue. I’d like to think it’s something like: “These kind folks help pay my salary, and I’m renting an apartment in Bay Ridge anyway, so it’s no big deal.” Or it could be something more “colorful.”

Within two years after this photo was taken, Kirby Higbe and the beloved Dixie Walker would be dealt to Pittsburgh. The deals shocked and outraged us. What we didn’t know was that Branch Rickey was building a new baseball dynasty in Brooklyn, and wanted harmony on his racially integrated team. We would lose the 1946 pennant race to the Cardinals in a playoff; but next season we would win the pennant, thanks in part to a rookie who played the game in an exciting, new way; a superb athlete and intense competitor with the kind of audacious baserunning skill we hadn’t seen before. I still have an old comic book devoted to him.

From 1947 on, baseball, Brooklyn, and America would be changed.

Dixie and Kirby (Part 1)

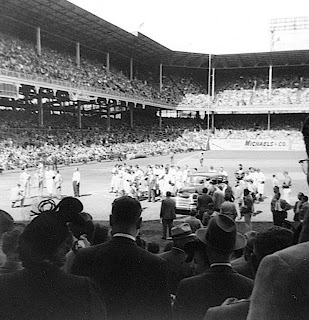

September 7, 1946: Ebbets Field, Dodgers vs. Giants, big crowd, red-hot pennant race with the Dodgers chasing the Cardinals. It was Ford Day; each Dodger was given a new automobile before the game. Ballplayers didn't make tons of money in those days, so these freebies meant something to them. My father’s friend worked for a big Ford dealership, so we got super-deluxe box seats. I asked (okay, told) Dad to snap the picture when Dixie Walker, my favorite Dodger, was presented with his car. The tall, balding, out-of-focus player standing behind home plate is Dixie. He was everyone's favorite. "The People's Choice," they called him -- or, as the sportswriters often put it, "the Peepul's Cherce."

We beat the Giants that day, 4-1. Kirby Higbe, our ace, pitched a one-hitter; the only Giants’ hit was a homerun by Ernie Lombardi. By the end of the day, we were just a game and a half out of first place.

As I look at it now, this photo has an elegiac quality. It’s the last month of the last season of pre-Jackie Robinson major league baseball. We didn't know it then, but our heroes Dixie Walker and Kirby Higbe had already expressed to management their unwillingness to play on the same team as a black man. We never suspected their days in Brooklyn were numbered. Eventually Walker’s views would evolve. Higbe himself later wrote that the coming of Jackie Robinson in 1947 was "the end of what you might call the Babe Ruth era and the beginning of modern professional baseball."

It’s true, it was the end of an era. At the time, we thought we were just watching a ballgame.

Thursday 24 February 2011

On the outside, looking in at Henry “Red” Allen

In the early and mid ‘50s a draft card was your passport to the magical land of jazz, and I was too young to have one. I was already hooked on the music. I had 78 rpm records (a pathetically small collection) and my first jazz LP (Benny Goodman’s Carnegie Hall concert). In other words, I knew nothing. And without a draft card, my experience with live jazz was limited to looking in from outside the Metropole Cafe on Broadway.

During the baseball off-season, we’d get our sports fix by going to Knicks games, college basketball doubleheaders, and indoor track meets at Madison Square Garden, the old Garden on 8th Avenue between 49th and 50th. We’d take the Sea Beach Express from Bay Ridge, get off at Times Square and stroll up Broadway. On the way home, we’d stroll down Broadway and invariably stop at the Metropole.

When weather permitted, they’d leave the doors open, and we’d join the cluster of tourists, deadbeats, teenagers, and deadbeat-teenagers on the sidewalk to dig the music. I remember clarinetists Tony Parenti and Sol Yaged being the headliners, but the band I remember most clearly was Red Allen, Coleman Hawkins, J.C. Higginbotham, Marty Napoleon, and Cozy Cole (basically the same personnel as on the Bluebird CD World on a String). If you stood real close, you could hear quite well. You could even hear customer comments from the bar; I remember a guy constantly requesting Ride, Red, Ride.

When weather permitted, they’d leave the doors open, and we’d join the cluster of tourists, deadbeats, teenagers, and deadbeat-teenagers on the sidewalk to dig the music. I remember clarinetists Tony Parenti and Sol Yaged being the headliners, but the band I remember most clearly was Red Allen, Coleman Hawkins, J.C. Higginbotham, Marty Napoleon, and Cozy Cole (basically the same personnel as on the Bluebird CD World on a String). If you stood real close, you could hear quite well. You could even hear customer comments from the bar; I remember a guy constantly requesting Ride, Red, Ride.

With my sideways view of the band, I could see no Cozy Cole, just brief glimpses of Hawkins, occasional flashes of a trombone slide. But you couldn’t miss Red Allen.

At the time, I knew nothing of Red's greatness or place in jazz history. I knew Higginbotham only because I had Louis Armstrong’s 1938 When the Saints Go Marching In (“Here comes Brother Higginbotham down the aisle with his trambone. Blow it, son!”). I knew Hawkins only because I had Hollywood Stampede with him, Vic Dickenson, Howard McGhee, et al. I had no idea Allen and Higginbotham were old cohorts. This was before historic reissues were abundant, so I’d never heard their fantastic records together from the 1930s. All I knew was that with Red Allen leading the band, there was always a party going on inside, and I was on the outside.

|

| Photograph by Lee Tanner |

At the time, I knew nothing of Red's greatness or place in jazz history. I knew Higginbotham only because I had Louis Armstrong’s 1938 When the Saints Go Marching In (“Here comes Brother Higginbotham down the aisle with his trambone. Blow it, son!”). I knew Hawkins only because I had Hollywood Stampede with him, Vic Dickenson, Howard McGhee, et al. I had no idea Allen and Higginbotham were old cohorts. This was before historic reissues were abundant, so I’d never heard their fantastic records together from the 1930s. All I knew was that with Red Allen leading the band, there was always a party going on inside, and I was on the outside.

"What neighborhood?"

Nobody’s just “from Brooklyn.” When people tell me they’re from Brooklyn, that’s not enough information. “What neighborhood?” is my immediate question. The borough is so big, its neighborhoods so distinct and diverse, that it’s a necessary question. Of the many Brooklyns, this was mine: 71st Street in Bay Ridge.

This photo was taken almost 25 years before I came along. It’s 1915. That’s my mother (at left) and a friend at the corner of 71st Street and Narrows Avenue, a half-block from Mom’s house, the same house I grew up in. Behind Mom, one block in the distance, is Shore Road; beyond Shore Road, the Narrows; beyond that, Staten Island.

The 18th century etching below, scanned from a book about the American Revolution, shows Lord Howe’s ships entering the Narrows in an attempt to trap and defeat General Washington’s ragtag army. (He failed.) I can see the familiar outline of Shore Road. I can almost pinpoint where we lived, a block and a half from the shore.

This photo was taken almost 25 years before I came along. It’s 1915. That’s my mother (at left) and a friend at the corner of 71st Street and Narrows Avenue, a half-block from Mom’s house, the same house I grew up in. Behind Mom, one block in the distance, is Shore Road; beyond Shore Road, the Narrows; beyond that, Staten Island.

The 18th century etching below, scanned from a book about the American Revolution, shows Lord Howe’s ships entering the Narrows in an attempt to trap and defeat General Washington’s ragtag army. (He failed.) I can see the familiar outline of Shore Road. I can almost pinpoint where we lived, a block and a half from the shore.

My mother’s family must have been among the first Jews to settle in Bay Ridge. Her father was a civil engineer who helped design the tunnel for the Fourth Avenue subway line leading to that almost-rural section of Brooklyn. The area appealed to him, and he moved the family there around 1910. When I was growing up in the 1940s and ‘50s, the neighborhood was largely Scandinavian-, Irish-, and Italian-American.

The block across the street and to the right in the photo is now the site of Xaverian High School. When I was a kid, there was nothing there, not even those rickety houses. It was an empty lot, one square block’s worth of weeds run wild and dead, decaying trees. In one corner was a tiny cemetary with tombstones from Revolutionary days. I wonder if any of the Colonials buried there were spectators the day Howe’s ships sailed into the Narrows. During and after World War II we called our lot “the jungle” (having seen too many war movies) and spent many a Saturday morning there, manfully fighting the Axis Powers. They built Xaverian on our jungle. The high school opened in 1956, the year I went away to college. I see on the Xaverian website that its first graduates, class of ’61, are about to hold their 50-year reunion. Yipes.

I’m happy about where I was born and when I was born. I’m not sure whom to thank for placing me in my particular place and time. Mom? Dad? My grandfather, for settling in Bay Ridge? I guess I should also thank Washington, for cleverly escaping Howe and making the whole thing possible. Way to go, George.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)